Laura Fermi’s Influence in Society

Laura Fermi speaks at Fermilab, 1974. Photo: FNAL.

Laura Fermi, a courageous and dedicated woman, published her New York Times bestseller Atoms in the Family, in 1954, the same year her husband Enrico died of stomach cancer, likely related to his work with unstable, radioactive elements. In 1955 she was the official U.S. historian to the first international conference on the peaceful uses of the atom.

Four years later, she and her girlfriends were looking at soot piling up on windowsills. Thinking globally and acting locally, Laura and her friends became pioneers in the environmental movement.

I found these two clippings (below) from 1970, among my grandmother’s papers. The first is about the tremendous impact a small group of women had at the time. They did not flinch when it came to questioning the very institutions employing their husbands. In the second clipping, Laura Fermi calls for repeal of a state of Illinois law requiring coal burning. Again she is a vanguard for clean air and clean energy.

A few years later, when she saw the environmental movement gaining momentum, Laura Fermi tackled another key public policy issue by starting the first gun control lobby in the United States: Civic Disarmament Committee for Handgun Control (CDC). She devoted herself to this cause until her death in 1977, including mentoring Mark Borinsky the founder of a national gun control lobby which is now the Brady Campaign to Prevent Gun Violence, the largest such group in the U.S.

Female warriors led first pollution battles

Chicago Today, Monday, March 2, 1970

Air pollution has become the greatest enemy of man’s environment. …The first parts of this series have shown the failures of pollution control. This report, the 13th in the series, is the first of three … [to] show … positive [results] in the pollution war.

In 1959, pollution was a little-used word for a little-known crusade. Yet, in that year, a small band of ardent Hyde Park [a southside neighborhood by the University of Chicago] women became probably the first — and most effective — citizens’ anti-pollution group in Chicago…

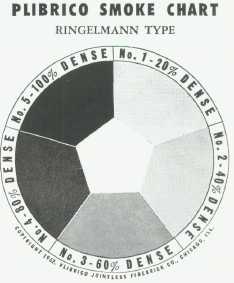

Laura Fermi and her pioneering air pollution control committee handed out cards like the one above to citizens so they could measure emissions violations in Chicago. There was a pentagonal hole cut out in the middle through which the viewer could gauge the density of the smoke and report it to authorities. Today’s methods for monitoring harmful emissions also analyze particulate contents. [Caption & image not part of original article]

Leader of the group was then, and is now, Mrs. Laura Fermi, widow of atomic scientist Enrico Fermi. Mrs. Fermi, a slight but tough woman with pragmatic ideas for ending pollution, recalled:

“We got started in our cleanup campaign because we saw pollution as a nuisance, as something depressing to the housewife. At first we saw it as dirt, not as a health hazard.

“Pollution was tiring for the housewife. It took energy to continuously wash and rewash clothes and sheets.”

Mrs. Fermi and her group which [numbered anywhere from 7-25], spent little time picketing or demonstrating, but drove to the heart of the issue — forcing violators to stop polluting.

“At one time we had 200 volunteers who were observing chimneys all over the neighborhood and spotting violations,” Mrs. Fermi said. “We prepared our own violation form. We gave it to the volunteers, who filled it out and sent it back to us. We sent it to the air pollution department, who took action.”

Under the organized, continual pressure, the department cited numerous Hyde-Park-Kenwood violators. … “We are sure that quite a number of buildings changed to gas permanently,” Mrs. Fermi said.

Thru the group’s 11 years, its main target has been the University of Chicago, the institution that employed many of the husbands of the pollution committee. The action against the university was not bitter, but the pressure was constant.

The pressure paid off several months ago when the university, which has considerable real estate holdings in the neighborhood, announced that it will convert all its property to gas or oil by 1971.

“I was at a formal party… ,” Mrs. Fermi recalls, “and I went up to … the university vice president, and asked him if he thought our needling had helped in the university’s decision. He said that it had. I got great satisfaction from that.”

Mrs. Fermi described other activities of the adamant women: “We talked to neighborhood groups and real estate agents. We made up lists for building janitors, telling them how to run their furnaces without polluting, and we told people how pollution affected their families…”

In 1962, members of the group gave dramatic testimony before a United States Senate committee that was contemplating grants on pollution. Mrs. Fermi said:

“One of our members testified, bringing with her a dirty handkerchief she had passed over a window shortly after she had washed the window.”

“Senator Edmund Muskie (D., ME) said it was the first time a citizens’ group had testified. We felt we helped Chicago. The city wound up with a one-million dollar pollution grant.”[Today that one-million dollar grant would be seven-million.] ?

Coal Law Repeal Urged

Chicago Sun-Times

January 6, 1970

MRS. LAURA FERMI, widow of atomic energy pioneer Enrico Fermi, urged a legislative committee to seek the repeal of a state law requiring public buildings to burn Illinois coal. The high sulphur content of Illinois coal is responsible for much of the state’s air pollution, said Mrs. Fermi.

Mrs. Fermi, representing the Cleaner Air Committee of Hyde Park and Kenwood, testified at a hearing by the Illinois House Air Pollution Study Committee in the State of Illinois building, 160. N. La Salle. She noted that the 1937 law forces public buildings to burn Illinois coal, even if the price is up to 10 per cent higher than other coal.

Her plea was echoed by Dr. Bruce Douglas, professor of community health at the University of Illinois college of Medicine, who called Illinois efforts to halt air pollution “lackadaisical”. He noted that Illinois budgeted only $125,923 for air pollution control during the last two years while New Jersey set aside $1,000,000 and New York appropriated $1,800,000.